While there has been incredible progress in convex and nonconvex minimization, a multitude of problems in ML today are in need of efficient algorithms to solve min-max optimization problems. Unlike minimization, where algorithms can always be shown to converge to some local minimum, there is no notion of a local equilibrium in min-max optimization that exists for general nonconvex-nonconcave functions. In two recent papers, we give two notions of local equilibria that are guaranteed to exist and efficient algorithms to compute them. In this post we present the key ideas behind a second-order notion of local min-max equilibrium from this paper and in the next we will talk about a different notion along with the algorithm and show its implications to GANs from this paper.

Min-max optimization

Min-max optimization of an objective function $f:\mathbb{R}^d \times \mathbb{R}^d \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$

\[\min_x \max_y f(x,y)\]is a powerful framework in optimization, economics, and ML as it allows one to model learning in the presence of multiple agents with competing objectives. In ML applications, such as GANs and adversarial robustness, the min-max objective function may be nonconvex-nonconcave. We know that min-max optimization is at least as hard as minimization, hence, we cannot hope to find a globally optimal solution to min-max problems for general functions.

Approximate local minima for minimization

Let us first revisit the special case of minimization, where there is a natural notion of an approximate second-order local minimum.

$x$ is a second-order $\varepsilon$-local minimum of $\mathcal{L}:\mathbb{R}^d\rightarrow \mathbb{R}$ if \(\|\nabla \mathcal{L}(x)\| \leq \varepsilon \ \ \mathrm{and} \ \ \nabla^2 \mathcal{L}(x) \succeq -\sqrt{\varepsilon}.\)

Now suppose we just wanted to minimize a function $\mathcal{L}$, and we start from any point which is not at an $\varepsilon$-local minimum of $\mathcal{L}$. Then we can always find a direction to travel in along which either $\mathcal{L}$ decreases rapidly, or the second derivative of $\mathcal{L}$ is large. By searching in such a direction we can easily find a new point which has a smaller value of $\mathcal{L}$ using only local information about the gradient and Hessian of $\mathcal{L}$. This means that we can keep decreasing $\mathcal{L}$ until we reach an $\varepsilon$-local minimum (see Nesterov and Polyak, here, here, and also an earlier blog post for how to do this with only access to gradients of $\mathcal{L}$). If $\mathcal{L}$ is Lipschitz smooth and bounded, we will reach an $\varepsilon$-local minimum in polynomial time from any starting point.

Is there an analogous definition with similar properties for min-max optimization?

Problems with current local optimality notions

There has been much recent work on extending theoretical results in nonconvex minimization to min-max optimization (see here, here, here, here, here. One way to extend the notion of local minimum to the min-max setting is to seek a solution point called a “local saddle”–a point $(x,y)$ where 1) $y$ is a local maximum for $f(x, \cdot)$ and 2) $x$ is a local minimum for $f(\cdot, y).$

For instance, this is used here, here, here, and here. But, there are very simple examples of two-dimensional bounded functions where a local saddle does not exist.

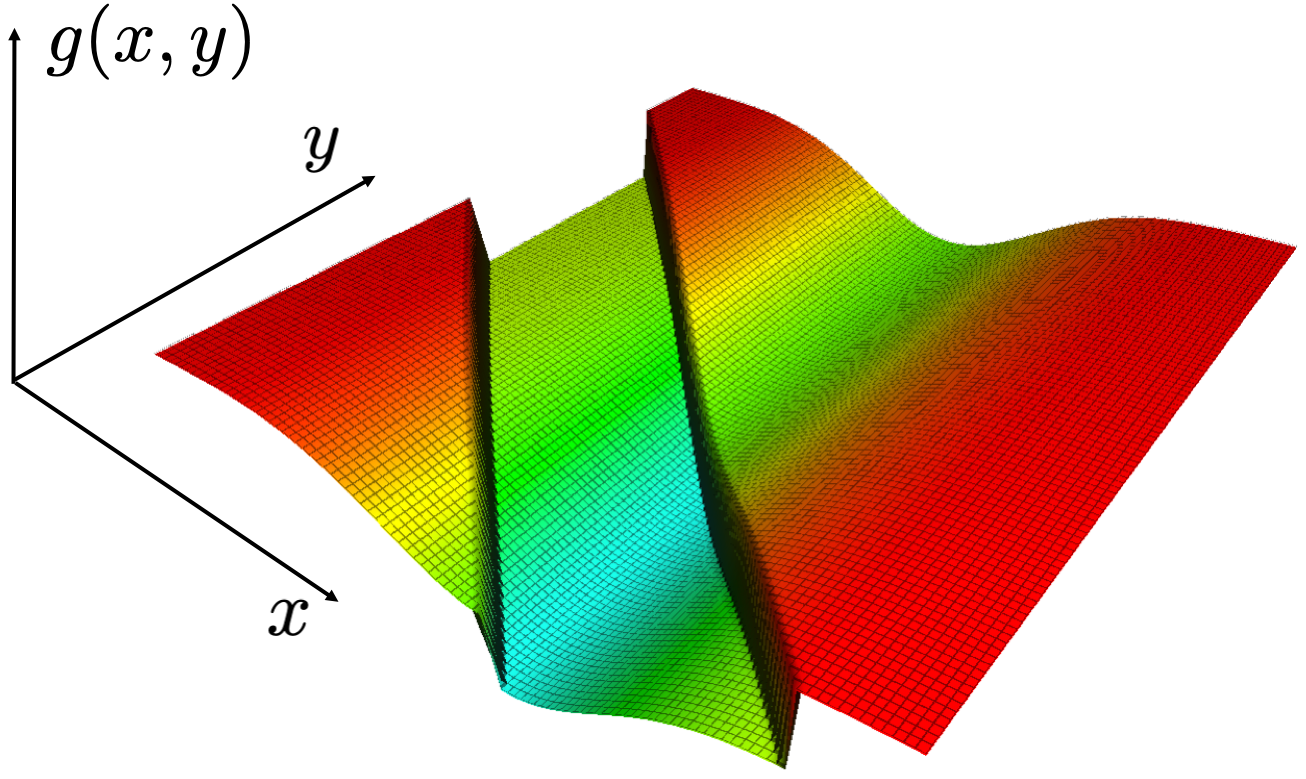

For instance, consider $f(x,y) = sin(x+y)$ from here. Check that none of the points on this function are simultaneously a local minimum for $x$ and local maximum for $y$.

The fact that no local saddle exists may be surprising, since an $\varepsilon$-global solution to a min-max optimization problem is guaranteed to exist as long as the objective function is uniformly bounded. Roughly, this is because, in a global min-max setting, the max-player is empowered to globally maximize the function $f(x,\cdot)$, and the min-player is empowered to minimize the “global max” function $\max_y(f(x, \cdot))$.

The ability to compute the global max allows the min-player to predict the max-player’s response. If $x$ is a global minimum of $\max_y(f(x, \cdot))$, the min-player is aware of this fact and will have no incentive to update $x$. On the other hand, if the min-player can only simulate the max-player’s updates locally (as in local saddle), then the min-player may try to update her strategy even when it leads to a net increase in $f$. This can happen because the min-player is not powerful enough to accurately simulate the max-player’s response. (See a related notion of local optimality with similar issues due to vanishingly small updates.)

The fact that players who can only make local predictions are

unable to predict their opponents’ responses can lead to convergence problems in many popular algorithms such as

gradient descent ascent (GDA). This non-convergence behavior can occur if the function has no local saddle point (e.g. the function $sin(x+y)$ mentioned above), and can even happen on some functions, like $f(x,y) = xy$ which do have a local saddle point.

Figure 1. GDA spirals off to infinity from almost every starting point on the objective function $f(x,y) = xy$.

Greedy max: a computationally tractable alternative to global max

To allow for a more stable min-player, and a more stable notion of local optimality, we would like to empower the min-player to more effectively simulate the max-player’s response. While the notion of global min-max does exactly this by having the min-player compute the global max function $\max_y(f(\cdot,y))$, computing the global maximum may be intractable.

Instead, we replace the global max function $\max_y (f(\cdot ,y))$ with a computationally tractable alternative. Towards this end, we restrict the max-player’s response, and the min-player’s simulation of this response, to updates which can be computed using any algorithm from a class of second-order optimization algorithms. More specifically, we restrict the max-player to updating $y$ by traveling along continuous paths which start at the current value of $y$ and along which either $f$ is increasing or the second derivative of $f$ is positive. We refer to such paths as greedy paths since they model a class of second-order “greedy” optimization algorithms.

Greedy path: A unit-speed path $\varphi:[0,\tau] \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^d$ is greedy if $f$ is non-decreasing over this path, and for every $t\in[0,\tau]$ \(\frac{\mathrm{d}}{\mathrm{d}t} f(x, \varphi(t)) > \varepsilon \ \ \textrm{or} \ \ \frac{\mathrm{d}^2}{\mathrm{d}t^2} f(x, \varphi(t)) > \sqrt{\varepsilon}.\)

Roughly speaking, when restricted to updates obtained from greedy paths, the max-player will always be able to reach a point which is an approximate local maximum for $f(x,\cdot)$, although there may not be a greedy path which leads the max-player to a global maximum.

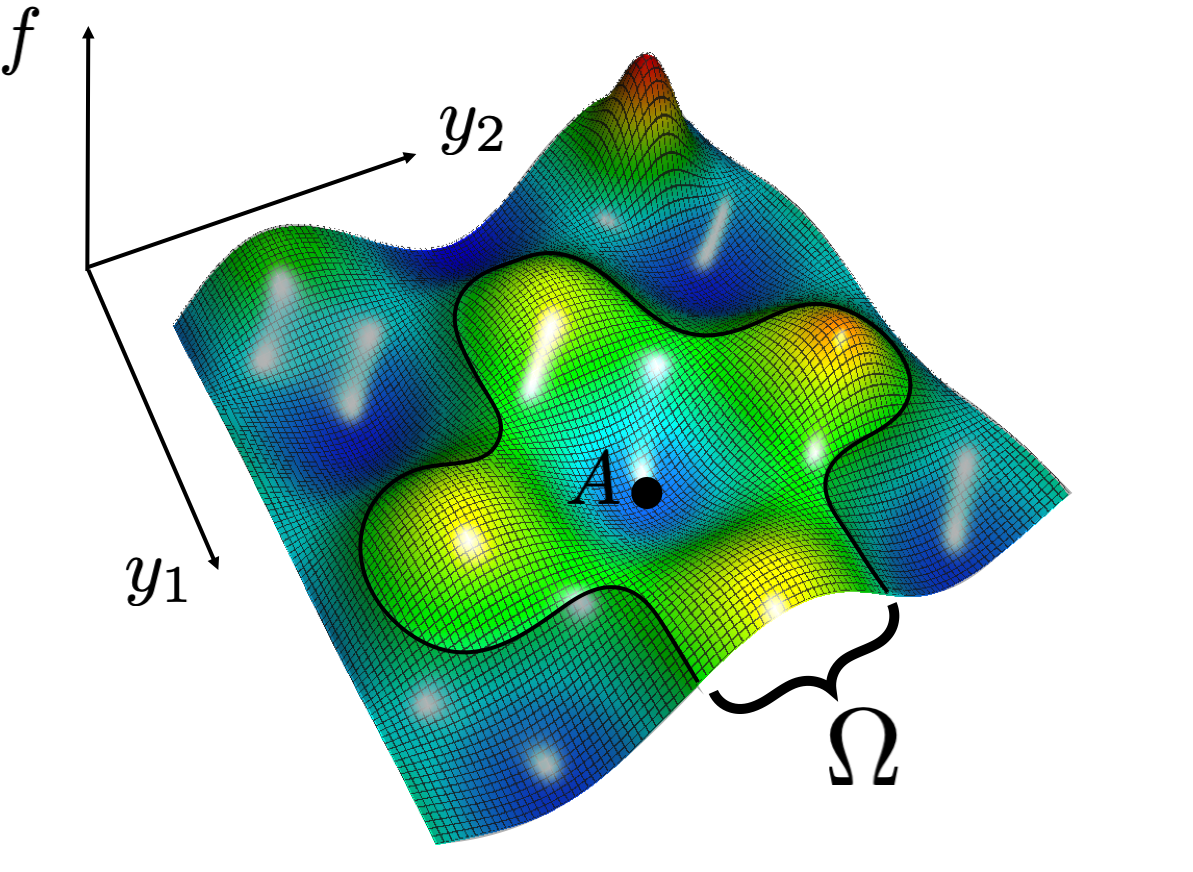

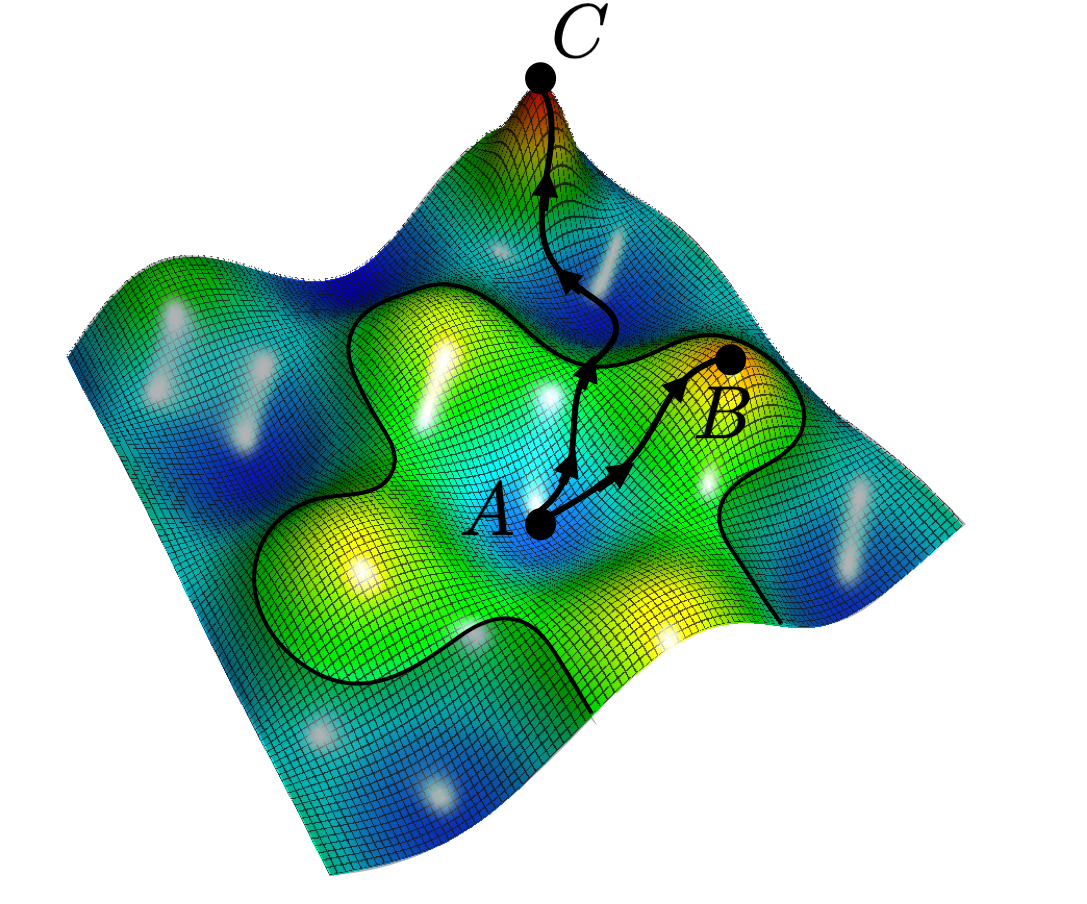

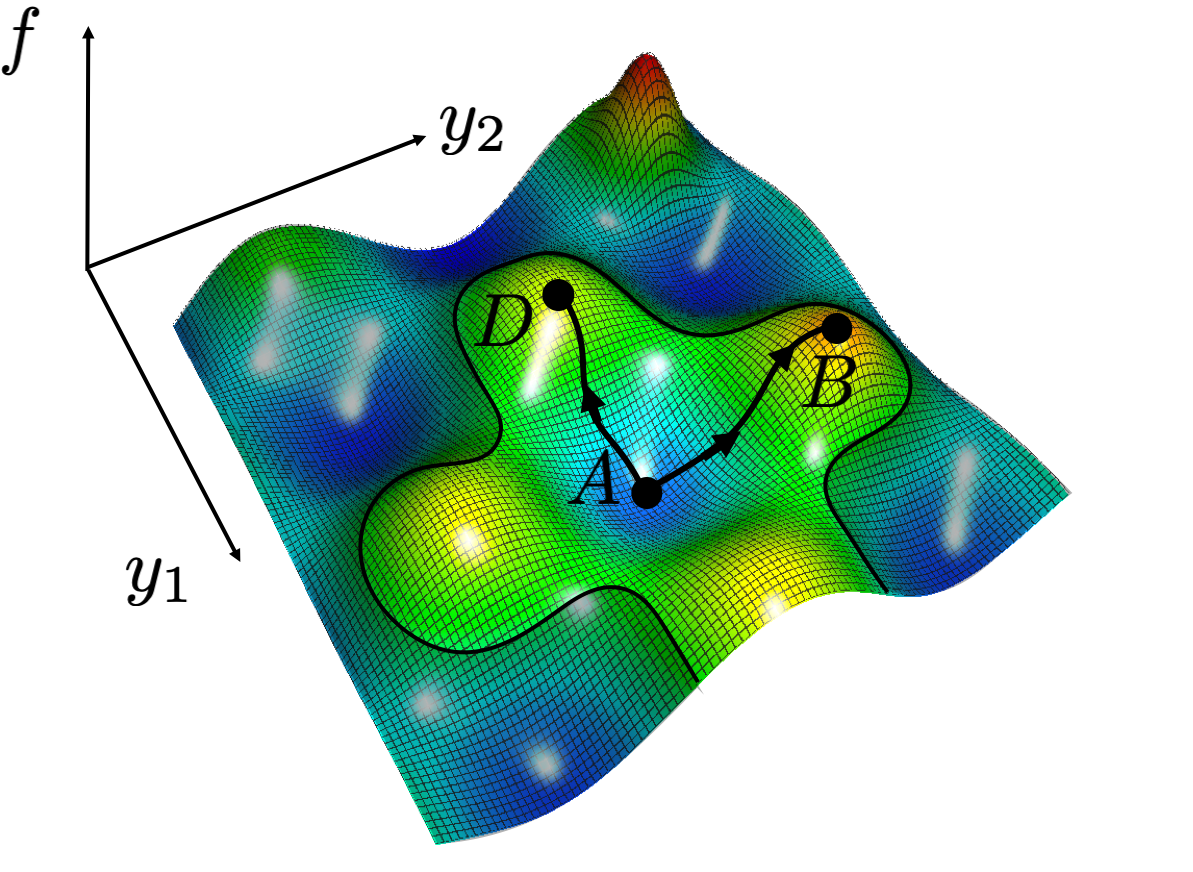

Figure 2. Left: The light-colored region $\Omega$ is reachable from the initial point $A$ by a greedy path; the dark region is not reachable. Right: There is always a greedy path from any point $A$ to a local maximum ($B$), but a global maximum ($C$) may not be reachable by any greedy path.

To define an alternative to $\max_y(f(\cdot,y))$, we consider the local maximum point with the largest value of $f(x,\cdot)$ attainable from a given starting point $y$ by any greedy path. We refer to the value of $f$ at this point as the greedy max function, and denote this value by $g(x,y)$.

Greedy max function: $g(x,y) = \max_{z \in \Omega} f(x,z),$ where $\Omega$ is points reachable from $y$ by greedy path.

Our greedy min-max equilibrium

We use the greedy max function to define a new second-order notion of local optimality for min-max optimization, which we refer to as a greedy min-max equilibrium. Roughly speaking, we say that $(x,y)$ is a greedy min-max equilibrium if 1) $y$ is a local maximum for $f(x,\cdot)$ (and hence the endpoint of a greedy path), and 2) if $x$ is a local minimum of the greedy max function $g(\cdot,y)$.

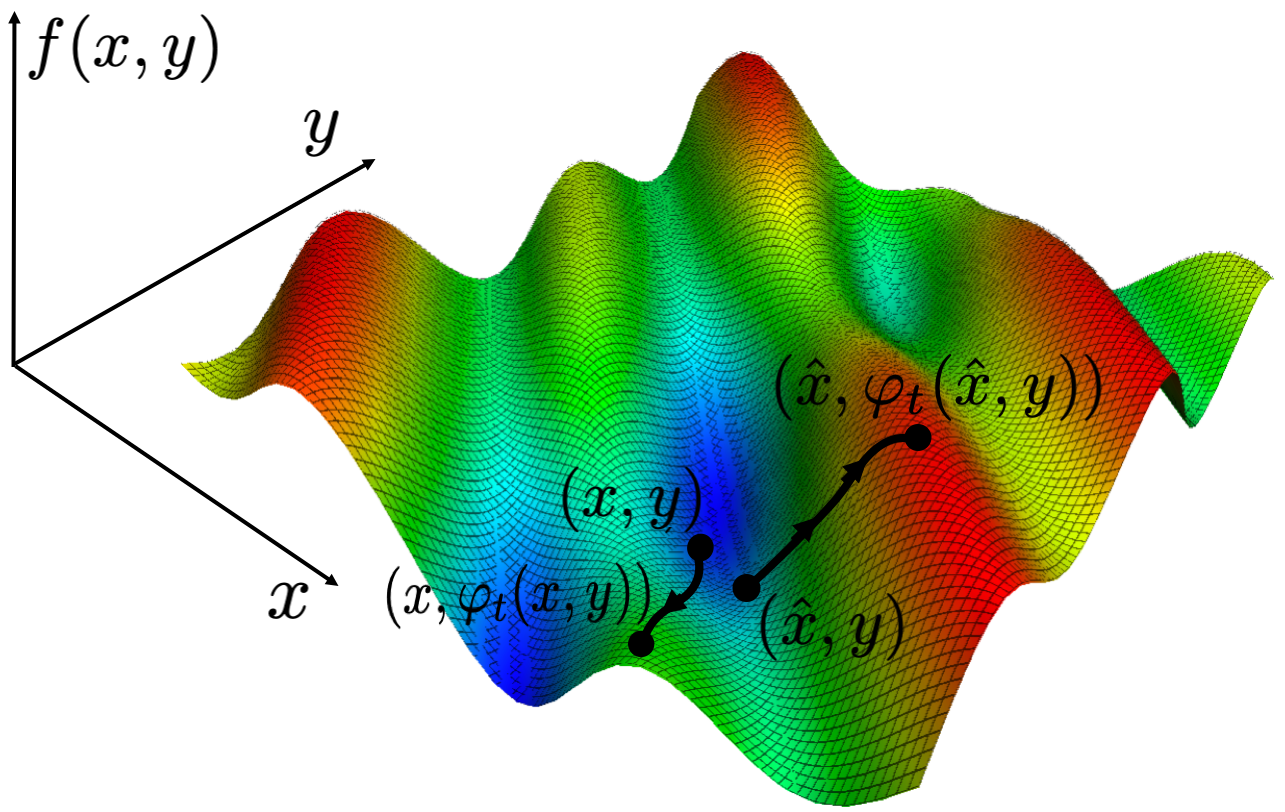

In other words, $x$ is a local minimum of $\max_y f(\cdot, y)$ under the constraint that the maximum is computed only over the set of greedy paths starting at $y$. Unfortunately, even if $f$ is smooth, the greedy max function may not be differentiable with respect to $x$ and may even be discontinuous.

Figure 3. Left: If we change $x$ from one value $x$ to a very close value $\hat{x}$, the largest value of $f$ reachable by greedy path undergoes a discontinuous change. Right: This means the greedy max function $g(x,y)$ is discontinuous in $x$.

This creates a problem, since the definition of $\varepsilon$-local minimum only applies to smooth functions.

To solve this problem we would ideally like to smooth $g$ by convolution with a Gaussian. Unfortunately, convolution can cause the local minima of a function to “shift”– a point which is a local minimum for $g$ may no longer be a local minimum for the convolved version of $g$ (to see why, try convolving the function $f(x) = x - 3x I(x\leq 0) + I(x \leq 0)$ with a Gaussian $N(0,\sigma^2)$ for any $\sigma>0$). To avoid this, we instead consider a “truncated” version of $g$, and then convolve this function in the $x$ variable with a Gaussian to obtain our smoothed version of $g$.

This allows us to define a notion of greedy min-max equilibrium. We say that a point $(x^\star, y^\star)$ is a greedy min-max equilibrium if $y^\star$ is an approximate local maximum of $f(x^\star, \cdot)$, and $x^\star$ is an $\varepsilon$-local minimum of this smoothed version of $g(\cdot, y^\star)$.

Greedy min-max equilibrium: $(x^{\star}, y^{\star})$ is an $\varepsilon$-greedy min-max equilibrium if

\(\|\nabla_y f(x^\star,y^\star)\| \leq \varepsilon, \qquad \nabla^2_y f(x^\star,y^\star) \preceq \sqrt{\varepsilon},\)

\(\|\nabla_x S(x^{\star},y^{\star})\| \leq \varepsilon \qquad \nabla^2_x S(x^{\star},y^{\star}) \succeq -\sqrt{\varepsilon}, \\\)

where $S(x,y):= \mathrm{smooth}_x(\mathrm{truncate}(g(x, y))$.

Any point which is a local saddle point (talked about earlier) also satisifeis our equilibrium conditions. The converse, however, cannot be true as a local saddle point may not always exist. Further, for compactly supported convex-concave functions a point is a greedy min-max equilibrium (in an appropriate sense) if and only if it is a global min-max point. (See Section 7 and Appendix A respectively in our paper.)

Greedy min-max equilibria always exist! (And can be found efficiently)

In this paper we show: A greedy min-max equilibrium is always guaranteed to exist provided that $f$ is uniformly bounded with Lipschitz Hessian. We do so by providing an algorithm which converges to a greedy min-max equilibrium, and, moreover, we show that it is able to do this in polynomial time from any initial point:

Main theorem: Suppose that we are given access to a smooth function $f:\mathbb{R}^d \times \mathbb{R}^d \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$ and to its gradient and Hessian. And suppose that $f$ is uniformly bounded by $b>0$ and has $L$-Lipschitz Hessian. Then given any initial point, our algorithm returns an $\varepsilon$-greedy min-max equilibrium $(x^\star,y^\star)$ of $f$ in $\mathrm{poly}(b, L, d, \frac{1}{\varepsilon})$ time.

There are a number of difficulties that our algorithm and proof must overcome: One difficulty in designing an algorithm is that the greedy max function may be discontinuous. To find an approximate local minimum of a discontinuous function, our algorithm combines a Monte-Carlo hill climbing algorithm with a zeroth-order optimization version of stochastic gradient descent. Another difficulty is that, while one can easily compute a greedy path from any starting point, there may be many different greedy paths which end up at different local maxima. Searching for the greedy path which leads to the local maximum point with the largest value of $f$ may be infeasible. In other words the greedy max function $g$ may be intractable to compute.

Figure 4.There are many different greedy paths that start at the same point $A$. They can end up at different local maxima ($B$, $D$), with different values of $f$. In many cases it may be intractable to search over all these paths to compute the greedy max function.

To get around this problem, rather than computing the exact value of $g(x,y)$, we instead compute a lower bound $h(x,y)$ for the greedy max function. Since we are able to obtain this lower bound by computing only a single greedy path, it is much easier to compute than greedy max function.

In our paper, we prove that if 1) $x^\star$ is an approximate local minimum for the this lower bound $h(\cdot, y^\star)$, and 2) $y^\star$ is a an approximate local maximum for $f(x^\star, \cdot)$, then $x^\star$ is also an approximate local minimum for the greedy max $g(\cdot, y^\star)$. This allows us to design an algorithm which obtains a greedy min-max point by minimizing the computationally tractable lower bound $h$, instead of the greedy max function which may be intractable to compute.

To conclude

In this post we have shown how to extend a notion of second-order equilibrium for minimization to min-max optimization which is guaranteed to exist for any function which is bounded and Lipschitz, with Lipschitz gradient and Hessian. We have also shown that our algorithm is able to find this equilibrium in polynomial time from any initial point.

Our results do not require any additional assumptions such as convexity, monotonicity, or sufficient bilinearity.

In an upcoming blog post we will show how one can use some of the ideas from here to obtain a new min-max optimization algorithm with applications to stably training GANs.