Today’s online world and the emerging internet of things is built around a Faustian bargain: consumers (and their internet of things) hand over their data, and in return get customization of the world to their needs. Is this exchange of privacy for convenience inherent? At first sight one sees no way around because, of course, to allow machine learning on our data we have to hand our data over to the training algorithm.

Similar issues arise in settings other than consumer devices. For instance, hospitals may wish to pool together their patient data to train a large deep model. But privacy laws such as HIPAA forbid them from sharing the data itself, so somehow they have to train a deep net on their data without revealing their data. Frameworks such as Federated Learning (Konečný et al., 2016) have been proposed for this but it is known that sharing gradients in that environment leaks a lot of information about the data (Zhu et al., 2019).

Methods to achieve some of the above so could completely change the privacy/utility tradeoffs implicit in today’s organization of the online world.

This blog post discusses the current set of solutions, how they don’t quite suffice for above questions, and the story of a new solution, InstaHide, that we proposed, and takeaways from a recent attack on it by Carlini et al.

Existing solutions in Cryptography

Classic solutions in cryptography do allow you to in principle outsource any computation to the cloud without revealing your data. (A modern method is Fully Homomorphic Encryption.) Adapting these ideas to machine learning presents two major obstacles: (a) (serious issue) huge computational overhead, which essentially rules it out for today’s large scale deep models (b) (less serious issue) need for special setups —e.g., requiring every user to sign up for public-key encryption.

Significant research efforts are being made to try to overcome these obstacles and we won’t survey them here.

Differential Privacy (DP)

Differential privacy (Dwork et al., 2006, Dwork&Roth, 2014) involves adding carefully calculated amounts of noise during training. This is a modern and rigorous version of classic data anonymization techniques whose canonical application is release of noised census data to protect privacy of individuals.

This notion was adapted to machine learning by positing that “privacy” in machine learning refers to trained classifiers not being dependent on data of individuals. In other words, if the classifier is trained on data from N individuals, it’s behavior should be essentially unchanged (statistically speaking) if we omit data from any individual. Note that this is a weak notion of privacy: it does not in any way hide the data from the company.

Many tech companies have adopted differential privacy in deployed systems but the following two caveats are important.

(Caveat 1): In deep learning applications, DP’s provable guarantees are very weak.

Applying DP to deep learning involves noticing that the gradient computation amounts to adding gradients of the loss corresponding to individual data points, and that adding noise to those individual gradients in calculated doses can help make the overall classifier limit its dependence on the individual’s datapoint.

In practice provable bounds require adding so much gradient noise that accuracy of the trained classifier plummets. We do not know of any successful training that achieved accuracy > 75 percent on CIFAR10 (or any that achieved accuracy even 10 percent on ImageNet). Furthermore, achieving this level of accuracy involves pretraining the classifier model on a large set of public images and then using the private/protected images only to fine-tune the parameters.

Thus it is no surprise that firms today usually apply DP with very low noise level, which give essentially no guarantees. Which brings us to:

(Caveat 2): DP’s guarantees (and even weaker guarantees applying to deployment scenarios) possibly act as a fig leaf that allows firms to not address the kinds of privacy violations that the person on the street actually worries about.

DP’s provable guarantee (which as noted, does not hold in deployed systems due to the low noise level used) would only ensure that a deployed ML software that was trained with data from tens of millions of users will not change its behavior depending upon private information of any single user.

But that threat model would seem remote to the person on the street. The privacy issue they worry about more is that copious amounts of our data are continuously collected/stored/mined/sold, often by entities we do not even know about. While lax regulation is primarily to blame, there is also the technical hurdle that there is no practical way for consumers to hide their data while at the same time benefiting from customized ML solutions that improve their lives.

Which brings us to the question we started with: Could consumers allow machine learning to be done on their data without revealing their data?

A proposed solution: InstaHide

InstaHide is a new concept: it hides or “encrypts” images to protect them somewhat, while still allowing standard deep learning pipelines to be applied on them. The deep model is trained entirely on encrypted images.

-

The training speed and accuracy is only slightly worse than vanilla training: one can achieve a test accuracy of ~ 90 percent on CIFAR10 using encrypted images with a computation overhead $< 5$ percent.

-

When it comes to privacy, like every other form of cryptography, its security is based upon conjectured difficulty of the underlying computational problem. (But we don’t expect breaking it to be as difficult as say breaking RSA.)

How InstaHide encryption works

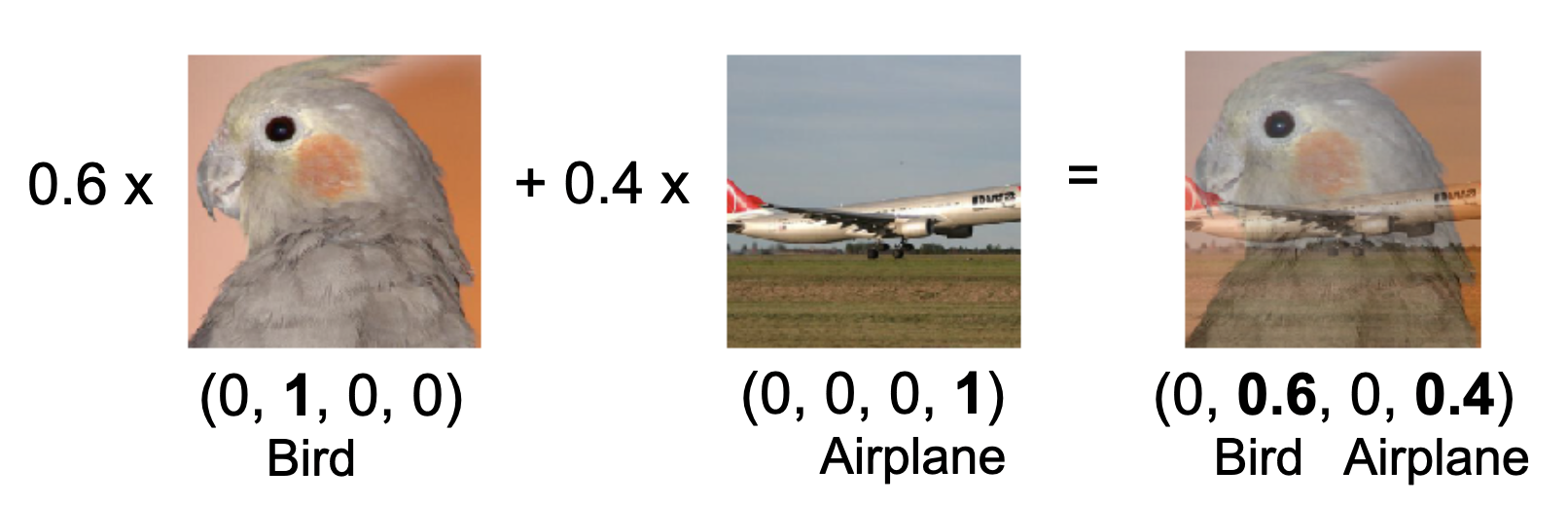

Here are some details. InstaHide belongs to the class of subset-sum type encryptions (Bhattacharyya et al., 2011), and was inspired by a data augmentation technique called Mixup (Zhang et al., 2018). It views images as vectors of pixel values. With vectors you can take linear combinations. The figure below shows the result of a typical MixUp: adding 0.6 times the bird image with 0.4 times the airplane image. The image labels can also be treated as one-hot vectors, and they are mixed using the same coefficients in front of the image samples.

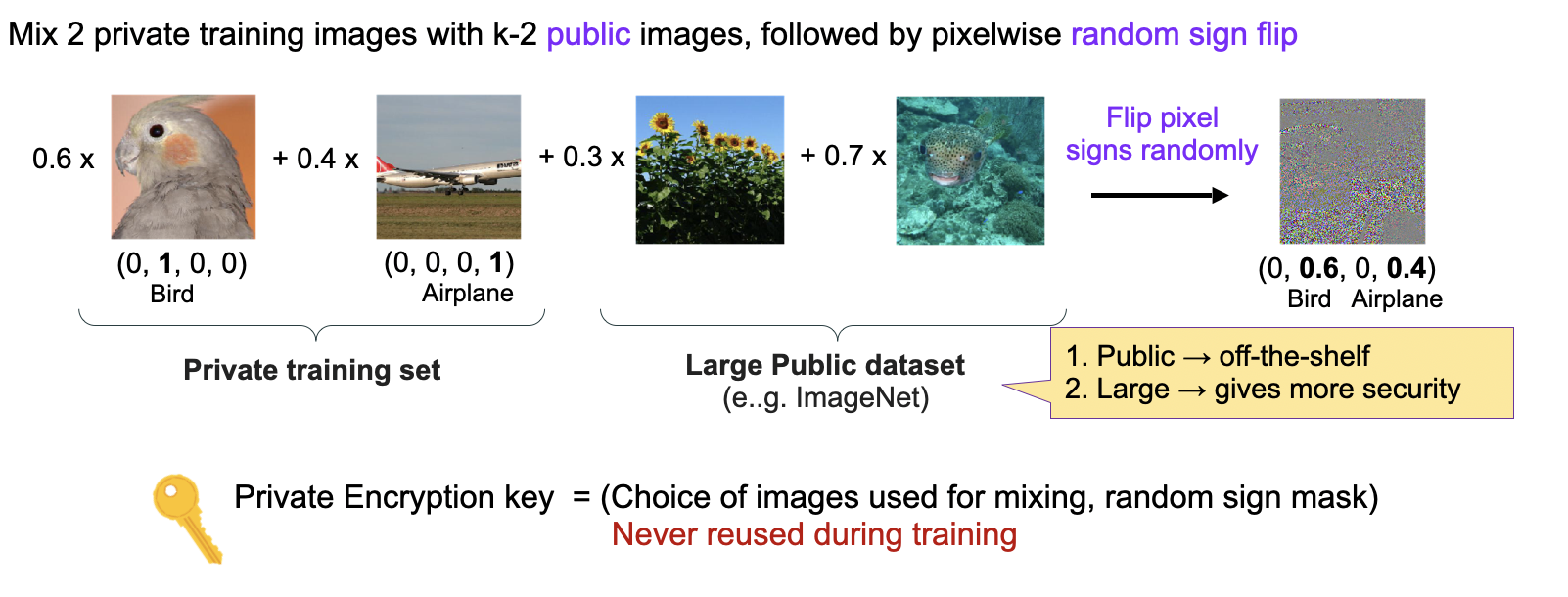

To encrypt the bird image, InstaHide does mixup (i.e., combination with nonnegative coefficients) with one other randomly chosen training image, and with two other images chosen randomly from a large public dataset like imagenet. The coefficients 0.6., 0.4 etc. in the figure are also chosen at random. Then it takes this composite image and for every pixel value, it randomly flips the sign. With that, we get the encrypted images and labels. All random choices made in this encryption act as a one-time key that is never re-used to encrypt other images.

InstaHide has a parameter $k$ denoting how many images are mixed; in the picture, we have $k=4$. The figure below shows this encryption mechanism.

When plugged into the standard deep learning with a private dataset of $n$ images, in each epoch of training (say $T$ epochs in total), InstaHide will re-encrypt each image in the dataset using a random one-time key. This will gives $n\times T$ encrypted images in total.

The security argument

We conjectured, based upon intuitions from computational complexity of the k-vector-subset-sum problem (citations), that extracting information about the images could time $N^{k-2}$. Here $N$, the size of the public dataset, can be tens or hundreds of millions, so it might be infeasible for real-life attackers.

We also released a challenge dataset with $k=6, n=100, T=50$ to enable further investigation of InstaHide’s security.

Carlini et al.’s recent attack on InstaHide

Recently, Carlini et al. have shared with us a manuscript with a two-step reconstruction attack (Carlini et al., 2020) against InstaHide.

TL;DR: They used 11 hours on Google’s best GPUs to get partial recovery of our 100 challenge encryptions and 120 CPU hours to break the encryption completely. Furthermore, the latter was possible entirely because we used an insecure random number generator, and they used exhaustive search over random seeds.

Now the details.

The attack takes $n\times T$ InstaHide-encrypted images as the input, ($n$ is the size of the private dataset, $T$ is the number of training epochs), and returns a reconstruction of the private dataset. It goes as follows.

-

Map $n \times T$ encryptions into $n$ private images, by clustering encryptions of a same private image as a group. This is achieved by firstly building a graph representing pairwise similarity between encrypted images, and then assign each encryption a private image. In their implementation, they train a neural network to annotate pairwise similarity between encryptions.

-

Then, given the encrypted images and the mapping, they solve a nonlinear optimization problem via gradient desent to recover an approximation of the original private dataset.

Using Google’s powerful GPU, it took them 10 hours to train the neural network for similarity annotation, and about another hour to get an approximation of our challenge set of $100$ images with $k=6, n=100, T=50$. This gave them vaguely correct images, with significant unclear areas and color shift.

They also proposed a different strategy which abuses the vulnerability of NumPy and PyTorch’s random number generator (Aargh; we didn’t use a secure random number generator.) They did brute force search of $2^{32}$ possible initial random seeds, which allows them to reproduce the randomness during encryption, and thus perform a pixel-perfect reconstruction. As they reported, this attack takes 120 CPU hours (they parallelize across 100 cores to obtain the solution in a little over an hour). We will have this implementation flaw fixed in an updated version.

Thoughts on this attack

Though the attack is clever and impressive, we feel that the long-term take-away is still unclear for several reasons.

Variants of InstaHide seem to evade the attack.

The challenge set contained 50 encryptions each of 100 images. This corresponds to using encrypted images for 50 epochs. But as done in existing settings that use DP, one can pretrain the deep model using non-private images and then fine-tune it with fewer epochs of the private images. Using a similar pipeline DPSGD (Abadi et al., 2016), by pretraining a ResNet-18 on CIFAR100 (the public dataset) and finetuning for $10$ epochs on CIFAR10 (the private dataset) gives accuracy of 83 percent, still far better than any provable guarantees using DP on this dataset. Carlini et al.\ team conceded that their attack probably would not work in this setting.

Similarly using InstaHide purely at inference time (i.e., using ML, instead of training ML) still should be completely secure since only one encryption of the image is released. The new attack can’t work here at all.

InstaHide was never intended to be a mission-critical encryption like RSA (which by the way also has no provable guarantees).

InstaHide is designed to give users and the internet of things a light-weight encryption method that allows them to use machine learning without giving eavesdroppers or servers access to their raw data. There is no other cost-effective alternative to InstaHide for this application. If it takes Google’s powerful computers a few hours to break our challenge set of 100 images, this is not yet a cost-effective attack in the intended settings.

More important, the challenge dataset corresponded to an ambitious form of security, where the encrypted images themselves are released to the world. The more typical application is a Federated Learning (Konečný et al., 2016) scenario: the adversary observes shared gradients that are computed using encrypted images (he also has access to the trained model). The attacks in this paper do not currently apply to that scenario. This is also the idea in TextHide, an adaptation of InstaHide to text data.

Takeways

Users need lightweight encryptions that can be applied in real time to large amounts of data, and yet allow them to take benefit of Machine Learning on the cloud. Methods to do so could completely change the privacy/utility tradeoffs implicitly assumed in today’s tech world.

InstaHide is the only such tool right now, and we now know that it provides moderate security that may be enough for many applications.