This post is based on my recent paper with Noam Razin (to appear at NeurIPS 2020), studying the question of whether norms can explain implicit regularization in deep learning. TL;DR: we argue they cannot.

Implicit regularization = norm minimization?

Understanding the implicit regularization induced by gradient-based optimization is possibly the biggest challenge facing theoretical deep learning these days. In classical machine learning we typically regularize via norms, so it seems only natural to hope that in deep learning something similar is happening under the hood, i.e. the implicit regularization strives to find minimal norm solutions. This is actually the case in the simple setting of overparameterized linear regression $-$ there, by a folklore analysis (cf. Zhang et al. 2017), gradient descent (and any other reasonable gradient-based optimizer) initialized at zero is known to converge to the minimal Euclidean norm solution. A spur of recent works (see our paper for a thorough review) has shown that for various other models an analogous result holds, i.e. gradient descent (when initialized appropriately) converges to solutions that minimize a certain (model-dependent) norm. On the other hand, as discussed last year in posts by Sanjeev as well as Wei and myself, mounting theoretical and empirical evidence suggest that it may not be possible to generally describe implicit regularization in deep learning as minimization of norms. Which is it then?

A standard test-bed: matrix factorization

A standard test-bed for theoretically studying implicit regularization in deep learning is matrix factorization $-$ matrix completion via linear neural networks. Wei and I already presented this model in our previous post, but for self-containedness I will do so again here.

In matrix completion, we are given entries $\{ M_{i, j} : (i, j) \in \Omega \}$ of an unknown matrix $M$, and our job is to recover the remaining entries. This can be seen as a supervised learning (regression) problem, where the training examples are the observed entries of $M$, the model is a matrix $W$ trained with the loss: [ \qquad \ell(W) = \sum\nolimits_{(i, j) \in \Omega} (W_{i, j} - M_{i, j})^2 ~, \qquad\qquad \color{purple}{\text{(1)}} ] and generalization corresponds to how similar $W$ is to $M$ in the unobserved locations. In order for the problem to be well-posed, we have to assume something about $M$ (otherwise the unobserved locations can hold any values, and guaranteeing generalization is impossible). The standard assumption (which has many practical applications) is that $M$ has low rank, meaning the goal is to find, among all global minima of the loss $\ell(W)$, one with minimal rank. The classic algorithm for achieving this is nuclear norm minimization $-$ a convex program which, given enough observed entries and under certain technical assumptions (“incoherence”), recovers $M$ exactly (cf. Candes and Recht).

Matrix factorization represents an alternative, deep learning approach to matrix completion. The idea is to use a linear neural network (fully-connected neural network with linear activation), and optimize the resulting objective via gradient descent (GD). More specifically, rather than working with the loss $\ell(W)$ directly, we choose a depth $L \in \mathbb{N}$, and run GD on the overparameterized objective: [ \phi ( W_1 , W_2 , \ldots , W_L ) := \ell ( W_L W_{L - 1} \cdots W_1) ~. ~~\qquad~ \color{purple}{\text{(2)}} ] Our solution to the matrix completion problem is then: [ \qquad\qquad W_{L : 1} := W_L W_{L - 1} \cdots W_1 ~, \qquad\qquad\qquad \color{purple}{\text{(3)}} ] which we refer to as the product matrix. While (for $L \geq 2$) it is possible to constrain the rank of $W_{L : 1}$ by limiting dimensions of the parameter matrices $\{ W_j \}_j$, from an implicit regularization standpoint, the case of interest is where rank is unconstrained (i.e. dimensions of $\{ W_j \}_j$ are large enough for $W_{L : 1}$ to take on any value). In this case there is no explicit regularization, and the kind of solution GD will converge to is determined implicitly by the parameterization. The degenerate case $L = 1$ is obviously uninteresting (nothing is learned in the unobserved locations), but what happens when depth is added ($L \geq 2$)?

In their NeurIPS 2017 paper, Gunasekar et al. showed empirically that with depth $L = 2$, if GD is run with small learning rate starting from near-zero initialization, then the implicit regularization in matrix factorization tends to produce low-rank solutions (yielding good generalization under the standard assumption of $M$ having low rank). They conjectured that behind the scenes, what takes place is the classic nuclear norm minimization algorithm:

Conjecture 1 (Gunasekar et al. 2017; informally stated): GD (with small learning rate and near-zero initialization) over a depth $L = 2$ matrix factorization finds solution with minimum nuclear norm.

Moreover, they were able to prove the conjecture in a certain restricted setting, and others (e.g. Li et al. 2018) later derived proofs for additional specific cases.

Two years after Conjecture 1 was made, in a NeurIPS 2019 paper with Sanjeev, Wei and Yuping Luo, we presented empirical and theoretical evidence (see previous blog post for details) which led us to hypothesize the opposite, namely, that for any depth $L \geq 2$, the implicit regularization in matrix factorization can not be described as minimization of a norm:

Conjecture 2 (Arora et al. 2019; informally stated): Given a depth $L \geq 2$ matrix factorization, for any norm $\|{\cdot}\|$, there exist matrix completion tasks on which GD (with small learning rate and near-zero initialization) finds solution that does not minimize $\|{\cdot}\|$.

Due to technical subtleties in their formal statements, Conjectures 1 and 2 do not necessarily contradict. However, they represent opposite views on the question of whether or not norms can explain implicit regularization in matrix factorization. The goal of my recent work with Noam was to resolve this open question.

Implicit regularization can drive all norms to infinity

The main result in our paper is a proof that there exist simple matrix completion settings where the implicit regularization in matrix factorization drives all norms towards infinity. By this we affirm Conjecture 2, and in fact go beyond it in the following sense: (i) not only is each norm disqualified by some setting, but there are actually settings that jointly disqualify all norms; and (ii) not only are norms not necessarily minimized, but they can grow towards infinity.

The idea behind our analysis is remarkably simple. We prove the following:

Theorem (informally stated): During GD over matrix factorization (i.e. over $\phi ( W_1 , W_2 , \ldots , W_L)$ defined by Equations $\color{purple}{\text(1)}$ and $\color{purple}{\text(2)}$), if learning rate is sufficiently small and initialization sufficiently close to the origin, then the determinant of the product matrix $W_{1: L}$ (Equation $\color{purple}{\text(3)}$) doesn’t change sign.

A corollary is that if $\det ( W_{L : 1} )$ is positive at initialization (an event whose probability is $0.5$ under any reasonable initialization scheme), then it stays that way throughout. This seemingly benign observation has far-reaching implications. As a simple example, consider the following matrix completion problem ($*$ here stands for unobserved entry): [ \qquad\qquad \begin{pmatrix} * & 1 \newline 1 & 0 \end{pmatrix} ~. \qquad\qquad \color{purple}{\text{(4)}} ] Every solution to this problem, i.e. every matrix that agrees with its observations, must have determinant $-1$. It is therefore only logical to expect that when solving the problem using matrix factorization, the determinant of the product matrix $W_{L : 1}$ will converge to $-1$. On the other hand, we know that (with probability $0.5$ over initialization) $\det ( W_{L : 1} )$ is always positive, so what is going on? This conundrum can only mean one thing $-$ as $W_{L : 1}$ fits the observations, its value in the unobserved location (i.e. $(W_{L : 1})_{11}$) diverges to infinity, which implies that all norms grow to infinity!

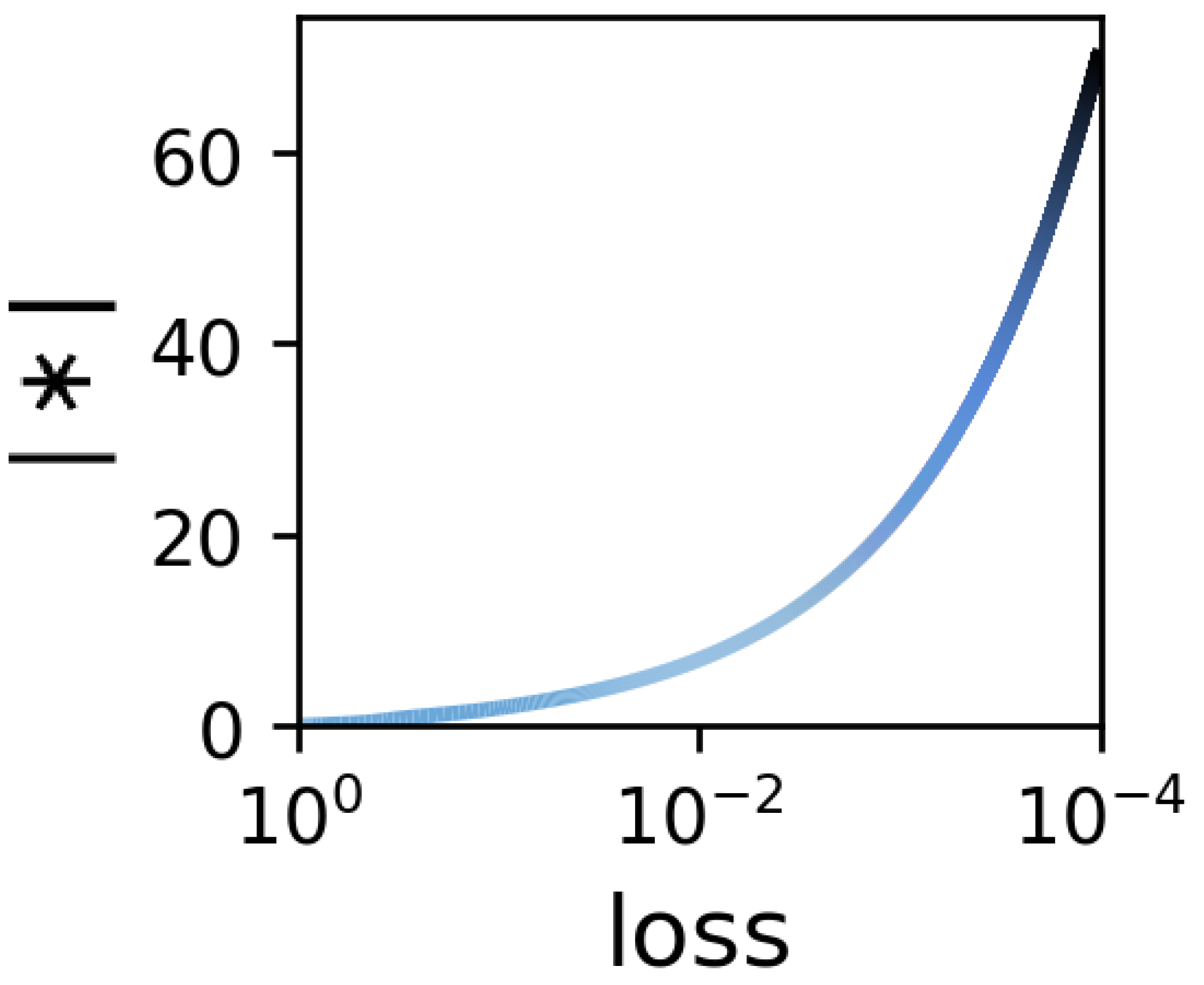

The above idea goes way beyond the simple example given in Equation $\color{purple}{\text(4)}$. We use it to prove that in a wide array of matrix completion settings, the implicit regularization in matrix factorization leads norms to increase. We also demonstrate it empirically, showing that in such settings unobserved entries grow during optimization. Here’s the result of an experiment with the setting of Equation $\color{purple}{\text(4)}$:

Figure 1: Solving matrix completion problem defined by Equation $\color{purple}{\text(4)}$ using matrix factorization leads absolute value of unobserved entry to increase (which in turn means norms increase) as loss decreases.

What is happening then?

If the implicit regularization in matrix factorization is not minimizing a norm, what is it doing? While a complete theoretical characterization is still lacking, there are signs that a potentially useful interpretation is minimization of rank. In our aforementioned NeurIPS 2019 paper, we derived a dynamical characterization (and showed supporting experiments) suggesting that matrix factorization is implicitly conducting some kind of greedy low-rank search (see previous blog post for details). This phenomenon actually facilitated a new autoencoding architecture suggested in a recent empirical paper (to appear at NeurIPS 2020) by Yann LeCun and his team at Facebook AI. Going back to the example in Equation $\color{purple}{\text(4)}$, notice that in this matrix completion problem all solutions have rank $2$, but it is possible to essentially minimize rank to $1$ by taking (absolute value of) unobserved entry to infinity. As we’ve seen, this is exactly what the implicit regularization in matrix factorization does!

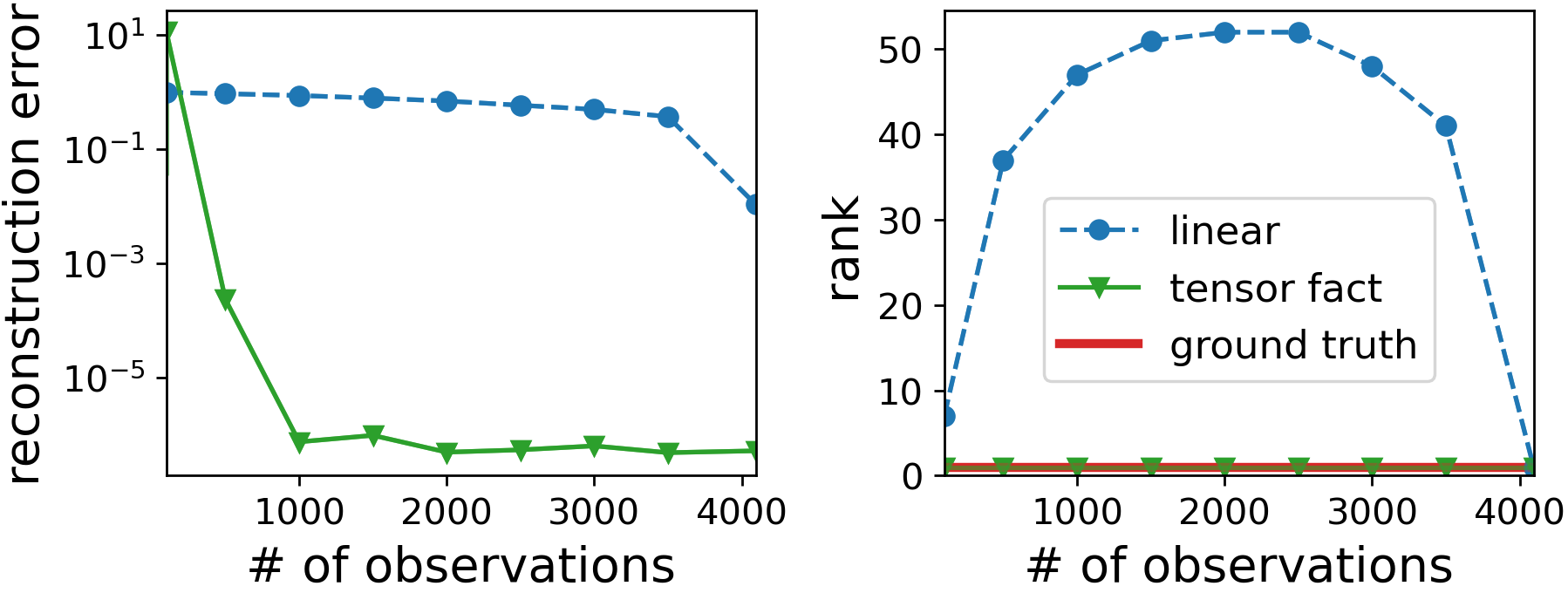

Intrigued by the rank minimization viewpoint, Noam and I empirically explored an extension of matrix factorization to tensor factorization. Tensors can be thought of as high dimensional arrays, and they admit natural factorizations similarly to matrices (two dimensional arrays). We found that on the task of tensor completion (defined analogously to matrix completion $-$ see Equation $\color{purple}{\text(1)}$ and surrounding text), GD on a tensor factorization tends to produce solutions with low rank, where rank is defined in the context of tensors (for a formal definition, and a general intro to tensors and their factorizations, see this excellent survey by Kolda and Bader). That is, just like in matrix factorization, the implicit regularization in tensor factorization also strives to minimize rank! Here’s a representative result from one of our experiments:

Figure 2: In analogy with matrix factorization, the implicit regularization of tensor factorization (high dimensional extension) strives to find a low (tensor) rank solution. Plots show reconstruction error and (tensor) rank of final solution on multiple tensor completion problems differing in the number of observations. GD over tensor factorization is compared against "linear" method $-$ GD over direct parameterization of tensor initialized at zero (this is equivalent to fitting observations while placing zeros in unobserved locations).

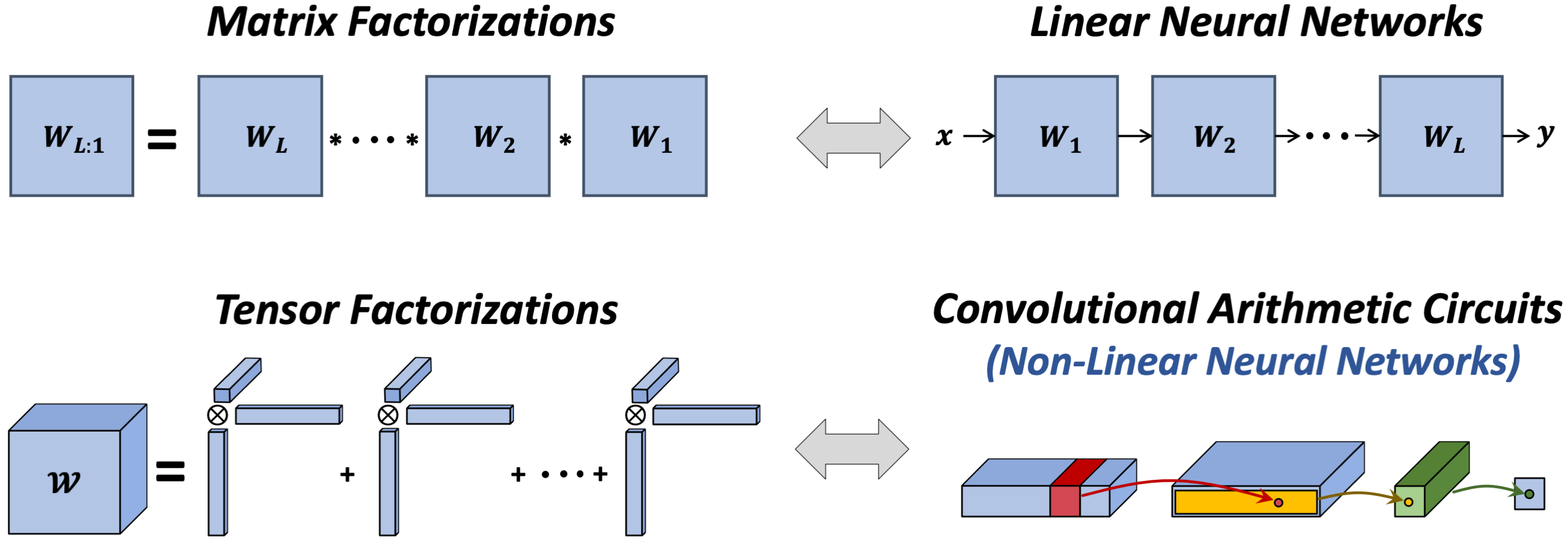

So what can tensor factorizations tell us about deep learning? It turns out that, similarly to how matrix factorizations correspond to prediction of matrix entries via linear neural networks, tensor factorizations can be seen as prediction of tensor entries with a certain type of non-linear neural networks, named convolutional arithmetic circuits (in my PhD I worked a lot on analyzing the expressive power of these models, as well as showing that they work well in practice $-$ see this survey for a soft overview).

Figure 3: The equivalence between matrix factorizations and linear neural networks extends to an equivalence between tensor factorizations and a certain type of non-linear neural networks named convolutional arithmetic circuits.

Analogously to how the input-output mapping of a linear neural network can be thought of as a matrix, that of a convolutional arithmetic circuit is naturally represented by a tensor. The experiment reported in Figure 2 (and similar ones presented in our paper) thus provides a second example of a neural network architecture whose implicit regularization strives to lower a notion of rank for its input-output mapping. This leads us to believe that implicit rank minimization may be a general phenomenon, and developing notions of rank for input-output mappings of contemporary models may be key to explaining generalization in deep learning.