Can you trust a model whose designer had access to the test/holdout set? This implicit question in Dwork et al 2015 launched a new field, adaptive data analysis. The question referred to the fact that in many scientific settings as well as modern machine learning (with its standardized datasets like CIFAR, ImageNet etc.) the model designer has full access to the holdout set and is free to ignore the

(Basic Dictum of Data Science) “Thou shalt not train on the test/holdout set.”

Furthermore, even researchers who scrupulously follow the Basic Dictum may be unknowingly violating it when they take inspiration (and design choices) from published works by others who presumably published only the best of the many models they evaluated on the test set.

Dwork et al. showed that if the test set has size $N$, and the designer is allowed to see the error of the first $i-1$ models on the test set before designing the $i$’th model, then a clever designer can use so-called wacky boosting (see this blog post) to ensure the accuracy of the $t$’th model on the test set as high as $\Omega(\sqrt{t/N})$. In other words, the test set could become essentially useless once $t \gg N$, a condition that holds in ML, whereby in popular datasets (CIFAR10, CIFAR100, ImageNet etc.) $N$ is no more than $100,000$ and the total number of models being trained world-wide is well in the millions if not higher (once you include hyperparameter searches).

Meta-overfitting Error (MOE) of a model is the difference between its average error on the test data and its expected error on the full distribution. (It is closely related to false discovery rate in statistics.)

This blog post concerns our new paper, which gives meaningful upper bounds on this sort of trouble for popular deep net architectures, whereas prior ideas from adaptive data analysis gave no nontrivial estimates. We call our estimate Rip van Winkle’s Razor which combines references to Occam’s Razor and the mythical person who fell asleep for 20 years.

Adaptive Data Analysis: Brief tour

It is well-known that for a model trained without ever querying the test set, MOE scales (with high probability over choice of the test set) as $1/\sqrt{N}$ where $N$ is the size of the test set. Furthermore standard concentration bounds imply that even if we train $t$ models without ever referring to the test set (in other words, using proper data hygiene) then the maximum meta-overfitting error among the $t$ models scales whp as $O(\sqrt{\log(t)/ N})$. The trouble pinpointed by Dwork et al. can happen only if models are designed adaptively, with test error of the previous models shaping the design of the next model.

Adaptive Data Analysis has come up with many good practices for honest researchers to mitigate such issues. For instance, Dwork et al. showed that using Differential Privacy on labels while evaluating models can lower MOE. Or the Ladder mechanism helps in Kaggle-like settings where the test dataset resides on a server that can choose to answers only a selected subset of queries, which essentially takes away the MOE issue.

For several good practices matching lower bounds exist showing a way to construct cheating models with MOE matching the upper bound.

However such recommended best practices do not help with understanding the MOE in the performance numbers of a new model since there is no guarantee that the inventors never tuned models using the test set, or didn’t get inspiration from existing models that may have been designed that way. Thus statistically speaking the above results still give no reason to believe that a modern deep net such as ResNet152 has low MOE.

Recht et al. 2019 summed up the MOE issue in a catchy title: Do ImageNet Classifiers Generalize to ImageNet? They tried to answer their question experimentally by creating new test sets from scratch –we discuss their results later.

MOE bounds and description length

The starting point of our work is the following classical concentration bounds:

Folklore Theorem With high probability over the choice of a test set of size $N$, the MOE of all models with description length at most $k$ bits is $O(\sqrt{k/N})$.

At first sight this doesn’t seem to help us because one cannot imagine modern deep nets having a short description. The most obvious description involves reporting values of the net parameters, which requires millions or even hundreds of millions of bits, resulting in a vacuous upper bound on MOE.

Another obvious description would be the computer program used to produce the model using the (publicly available) training and validation sets. However, these programs usually rely on imported libraries through layers of encapsulation and so the effective program size is pretty large as well.

Rip van Winkle’s Razor

Our new upper bound involves a more careful definition of Description Length: it is the smallest description that allows a referee to reproduce a model of similar performance using the (universally available) training and validation datasets.

While this phrasing may appear reminiscent of the review process for conferences and journals, there is a subtle difference with respect to what the referee can or cannot be assumed to know. (Clearly, assumptions about the referee can greatly affect description length —e.g, a referee ignorant of even basic calculus might need a very long explanation!)

Informed Referee: “Knows everything that was known to humanity (e.g., about deep learning, mathematics,optimization, statistics etc.) right up to the moment of creation of the Test set.”

Unbiased Referee: Knows nothing discovered since the Test set was created.

Thus Description Length of a model is the number of bits in the shortest description that allows an informed but unbiased referee to reproduce the claimed result.

Note that informed referees let descriptions get shorter. Unbiased require longer descriptions that rule out any statistical “contamination” due to any interaction whatsoever with the test set. For example, momentum techniques in optimization were well-studied before the creation of ImageNet test set, so informed referees can be expected to understand a line like “SGD with momentum 0.9.” But a line like “Use Batch Normalization” cannot be understood by unbiased referees since conceivably this technique (invented after 2012) might have become popular precisely because it leads to better performance on the test set of ImageNet.

By now it should be clear why the estimate is named after “Rip van Winkle”: the referee can be thought of as an infinitely well-informed researcher who went into deep sleep at the moment of creation of the test set, and has just been woken up years later to start refereeing the latest papers. Real-life journal referees who luckily did not suffer this way should try to simulate the idealized Rip van Winkle in their heads while perusing the description submitted by the researcher.

To allow as short a description as possible the researcher is allowed to compress the description of their new deep net non-destructively using any compression that would make sense to Rip van Winkle (e.g., Huffman Coding). The description of the compression method itself is not counted towards the description length – provided the same method is used for all papers submitted to Rip van Winkle. To give an example, a technique appearing in a text known to Rip van Winkle could be succinctly referred to using the book’s ISBN number and page number.

Estimating MOE of ResNet-152

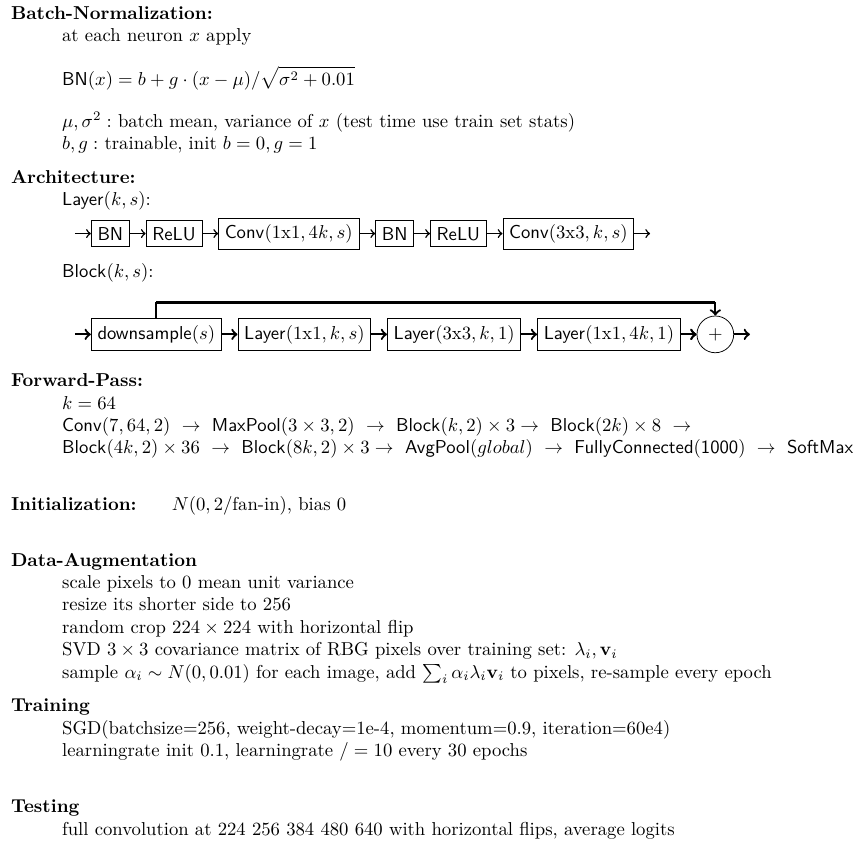

As an illustration, here we provide a suitable description allowing Rip van Winkle to reproduce a mainstream ImageNet model, ResNet-152, which achieves $4.49\%$ top-5 test error.

The description consists of three types of expressions: English phrases, Math equations, and directed graphs. In the paper, we describe in detail how to encode each of them into binary strings and count their lengths. The allowed vocabulary includes primitive concepts that were known before 2012, such as CONV, MaxPool, ReLU, SGD etc., as well as a graph-theoretic notation/shorthand for describing net architecture. The newly introduced concepts including Batch-Norm, Layer, Block are defined precisely using Math, English, and other primitive concepts.

According to our estimate, the length of the above description is $1032$ bits, which translates into a upper bound on meta-overfitting error of merely $5\%$! This suggests the real top-5 error of the model on full distribution is at most $9.49\%$. In the paper we also provide a $980$-bit long description for reproducing DenseNet-264, which leads to $5.06\%$ upper bound on its meta-overfitting error.

Note that the number $5.06$ suggests higher precision than actually given by the method, since it is possible to quibble about the coding assumptions that led to it. Perhaps others might use a more classical coding mechanism and obtain an estimate of $6\%$ or $7\%$.

But the important point is that unlike existing bounds in Adaptive Data Analysis, there is no dependence on $t$, the number of models that have been tested before, and the bound is non-vacuous.

Empirical evidence about lack of meta-overfitting

Our estimates indicate that the issue of meta-overfitting on ImageNet for these mainstream models is mild. The reason is that despite the vast number of parameters and hyper-parameters in today’s deep nets, the information content of these models is not high given knowledge circa 2012.

Recently Recht et al. tried to reach an empirical upper bound on MOE for ImageNet and CIFAR-10. They created new tests sets by carefully replicating the methodology used for constructing the original ones. They found that error of famous published models of the past seven years is as much as 10-15% higher on the new test set as compared to the original. On the face of it, this seemed to confirm a case of bad meta-overfitting. But they also presented evidence that the swing in test error was due to systemic effects during test set creation. For instance, a comparable swing happens also for models that predated the creation of ImageNet (and thus were not overfitted to the ImageNet test set). A followup study of a hundred Kaggle competitions used fresh, identically distributed test sets that were available from the official competition organizers. The authors concluded that MOE does not appear to be significant in modern ML.

Conclusions

To us the disquieting takeaway from Recht et al.’s results was that estimating MOE by creating a new test set is rife with systematic bias at best, and perhaps impossible, especially in datasets concerning rare or one-time phenomena (e.g., stock prices). Thus their work still left a pressing need for effective upper bounds on meta-overfitting error. Our Rip van Winkle’s Razor is elementary, and easily deployable by the average researcher. We hope it becomes part of the standard toolbox in Adaptive Data Analysis.